Despite zero visibility and hazardous conditions, the reconstruction of a dock structure at the Port of Beaumont, Texas, will be completed this month, six months ahead of schedule.

Using custom “punches” and a playbook to react nimbly to unforeseen conditions and ever-changing scenarios, crews on the $57 million project led by McCarthy Building Cos. removed a partially collapsed pier that sat atop an older pier and built a larger pier at the fourth-busiest US shipping port.

With so many risks and unknowns, the team created a contingency plan notebook. “We set parameters for what we could do without re-engineering and approval, say up to 5 feet in any direction or reinforcing reinforcement in a cap if needed,” he says. Robert Wood, McCarthy Senior Project Manager.

Kevin Drouet, an engineer with Lanier & Associates Consulting Engineers Inc., says the manual was helpful most of the time. “It gave direction to the field crews so they could work without looking for direction again. We anticipated on almost every mound that there was potential to not be driven to the existing location due to unknowns. In the design, we built flexibility into stack locations so we could switch.”

When McCarthy won the bid to rebuild the port’s Main Street Terminal 1, crews encountered a concrete pier that had partially collapsed due to steel piling corrosion. “It was a massive structure that collapsed in different ways,” says Wood. “A lot of it was under water. What was down there? What’s the state of the dock?”

Before removal began, the project team had to do some research, including using photos of the original wooden pier from a museum, he says. “It was built in the early 1900s and ironically, it was still intact,” says Wood.

Navigating a murky past

In the 1950s, the concrete pier was built on top of the wooden pier. “We had hand-drawn drawings” of that dock, which included railroad tracks. In each bent pile, 60 of them, were four steel piles covered with concrete, creating solid walls that rose 10 feet to the deck. Each wall was 3 feet wide, 40 feet long, and 10 feet high.

A couple of piles corroded so much that the weight of those walls became interconnected, Wood says.

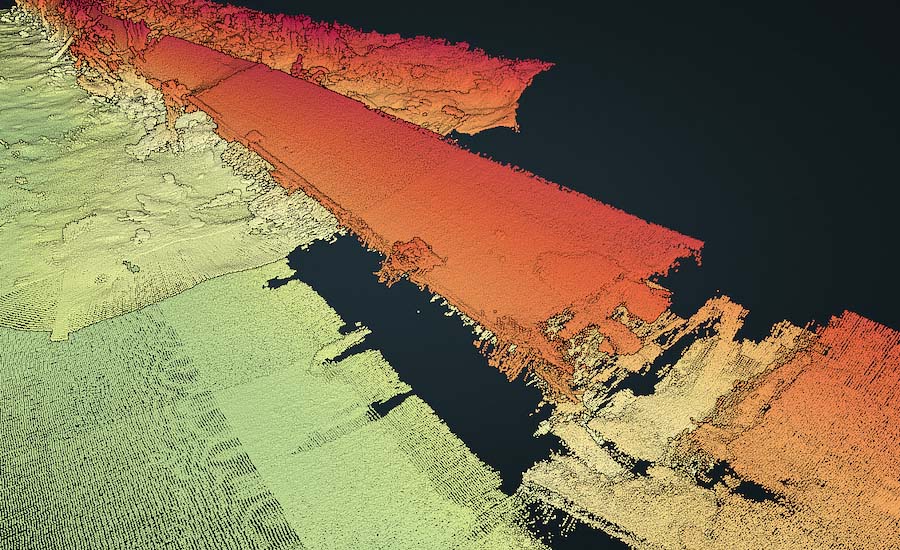

Underwater maps helped identify the extent of damage to the pier.

Underwater maps helped identify the extent of damage to the pier.Image courtesy of McCarthy Building Cos.

All the walls remained intact while the piles began to collapse. The east end of the pier collapsed but was on a flat plane and a decent slope, he recalls. “As you went west, the face of the pier started to slope lower; almost vertical.”

Before crews could begin installing piles for the new 300-foot-long, 130-foot-wide pier, they had to figure out how to safely demolish and dispose of the concrete structure, aware of the potential for more failures during the work. The divers had to navigate the murky depths of the Naches River, often only walking through a jungle of concrete and steel.

“At the far east end, we sent divers out to touch and they went up and validated what we had [mapped]” Wood said.

McCarthy made a variety of demolition tools, called punches. “We tried a variety; first we had a torpedo-looking accord that weighed 20,000 pounds,” says Wood.

Crews dropped it to try to break the dock. It was effective, sort of, says Wood. “But once underwater, where does it go? We needed constant feedback.”

McCarthy designed a “punch” to aid in the demolition of the pier

McCarthy designed a “punch” to aid in the demolition of the pierPhoto courtesy of McCarthy Building Cos.

Another punch consisted of an approximately 40-foot pile with a welded steel tip, filled with concrete, strategically dropped to break sections of decking. The challenge was to be precise to avoid creating more debris underwater.

After encountering a wall that had moved 10 feet on the east end, crews used a “guided” auger, taking the original stack and placing it inside another stack of pipes. “We had a crane hold the pile so we could pull the punch inside,” says Wood. “Then you could hold the outer tube steady and pick it up and drop it like a piston.”

As crews moved west with the demolition, “we fixed some legs on our guide stack so that it almost sat on the deck and held on to cut the deck vertically,” adds Wood.

With most of one wall under mud, McCarthy slid the rig down 40 feet, chained the wall and pulled it out while navigating unknown underwater conditions. Crews constantly discovered unexpected obstructions, including a concrete seawall, boulders and remnants of the two older piers. Using a shore-side crane, “we took the old torpedo hit and broke and hammered it all the way down and removed the [concrete] slab topped like a can opener”.

The 18-inch diameter wooden pier piles were spaced every 3 inches. “We had to take several of them out at once,” says Wood. Divers clamped the batteries and crews used a vibratory hammer to remove them.

The new prestressed concrete piles are 30 inches x 30 inches square, up to 140 feet and weighing up to 45 tons. In a quest to minimize equipment sizes, the stacks were originally designed with gaps about two-thirds of the length, but they began to crack during installation, Wood says. Eventually, the team changed them to solid piles 90 feet long. “A big concern was how to get all the debris out of there to make room for new batteries,” says Wood. Also, there was the risk of sinking a new pile into the mud and losing it entirely. “We spent a lot of time collecting in the mud.”

The new pier is the largest piece of the “most robust capital program ever” for the port, at about $400 million, says Brandon Bergeron, its director of engineering. “We’re building a few more docks, a major rail expansion and planning 30 new acres of storage and 10 acres of truck tailing areas.”